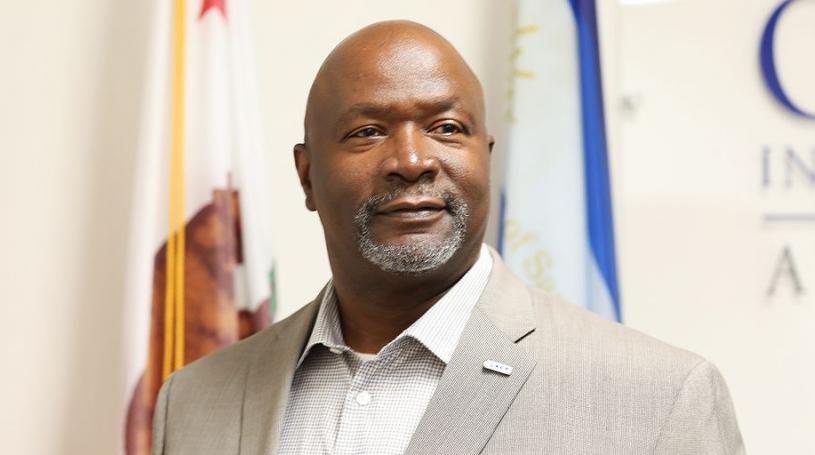

BRUCE ATLAS HAS BIG ROLE IN ONTARIO AIRPORT RENAISSANCE

By Dianne Anderson

Working the family limousine business in the late 1980’s, Bruce Atlas, Chief Operating Officer for the Ontario International Airport Authority, was not looking for a job, and he had no background in aviation.

He did, however, have a commitment to pay life forward by mentoring a young man at a job fair. While he waited outside for the youth to drop off resumes, he didn’t realize he was joking with a Southwest Airline recruiter.

“He said, you have a great personality, you’ll be a great fit. I said, No, I’m not interested, but there’s this young man. He said we’ll hire him and you too,” Atlas said.

Despite declining several offers, he felt something deep down inside calling for him to say yes.

His first few weeks on the job seemed less about aviation and more about counseling. His supervisor was on the verge of suicide, going through a divorce. Atlas, a cargo agent, was there to listen and talk, just one human being to another.

Back then, at the Southwest Los Angeles operation, he worked his way up, revising training policies, even as his union representative complained that he was working outside of his job title. That problem was soon resolved when Atlas was promoted to supervisor.

Committed to the company, Atlas set out to fix the biggest challenge he saw, to improve employee morale and company production. His idea for a barbecue competition was a hit to reduce luggage charge-backs. It could help save the airlines some of the millions of dollars they were losing annually to recover bags that didn’t make it on the flight.

“We started a competition with our sister city. Whoever lost would have to fly up to Oakland and barbecue for their team. If they lost, [Oakland workers] would come down to Los Angeles,” he said.

The other big problem is that the Los Angeles station had a bad reputation. Pilots and crews didn’t want to get off the plane, so he included a few sentences in all internal letters, asking workers to help make their station a winning station. That year, Los Angeles International Airport, won station of the year.

As the company restructured for its mega-station, he said the daily commute from the Inland Empire was a drain. He stopped by the Ontario office to see if he could transfer locally.

“I could have been fluent in 14 different languages from the time I spent on the freeway,” he said. “I was going to resign.”

But again, within a few months, he was up for a promotion. The person in charge of Ontario moved away to another region, opening up that position. He was assigned as Southwest general station manager with 183 employees, where he continued to work in Ontario for the following 13 years.

In the tough times, attitude was everything. He remembers wearing a Hawaiian shirt on the job, and would often go to the counter to help customers, or he’d stand back to observe how his workers were treating the customers. Customers would approach him to ask if his supervisor was available.

He’d offer to help.

“They would say, ‘No, I want to talk to your supervisor.’ I had to explain that in Ontario, this is it – unless you want to reach out to Dallas, Texas,” he said.

In 2016, just as he planned to retire from the Southwest station, and move to Charlotte, he received yet another call from on high, asking him to take the position as Chief Operating Officer for the Ontario International Airport Authority.

Today, with two decades aviation experience, Atlas is in charge of day to day operations at the airport, safety and security, fire and police, airfield operations and maintenance, and terminal operations.

For young people today moving up, his advice is chin up.

“There are some people that would say your attitude will determine your altitude,” he said. “If you have likability, sometimes people see you in positions that you didn’t see yourself.”

He is number ten of 11 children, who grew up in a two bedroom, one bath home in Watts. He remembers sleeping on the front porch with no air conditioner on hot summer nights. He remembers the riots, the military tanks up and down the streets.

It taught him a lot about where he didn’t want to spend the rest of his life.

Even then, there were good memories when his scoutmaster would come to take him and other local kids to places like Disneyland, or they’d go camping. Most people in the inner city never venture outside their six-mile radius.

Up the ladder through many promotions, he counts one of his most important accomplishment in founding the Marcus Heart Foundation, a nonprofit youth motivation program named after his 19-year-old son who was killed in Afghanistan, Army 82nd airborne infantry in 2009.

This year, the program’s website announced the organization raised $42,000 to help students with mentoring, scholarships, meals and tuition.

In 2010, he set up the foundation and task force to encourage young people to focus on education goals and be aware that the choices they make can impact them for a lifetime. He reaches students with scholarships, along with his wife Dana, a nurse, who works to help with meal plans and brain nutrition.

Since starting in Ontario after the 9/11 attacks, he said they didn’t allow tourism at the airport, but he pressed to bring inner city kids in to let them experience the operations.

Among his many contributions and community service, Atlas is chairman of the Inland Empire Regional Chamber of Commerce.

“The youth are our future, we have to invest in them,” he said.